In 1996 Congress passed the first major re-writing of communications regulations since 1934, the comprehensive Telecom Act. Unfortunately, according to many observers and players, this legislation was almost obsolete by the time it became law. The telecommunication industry has come so far so fast, that the laws and regulations within the Telecom Act are simply no longer applicable.

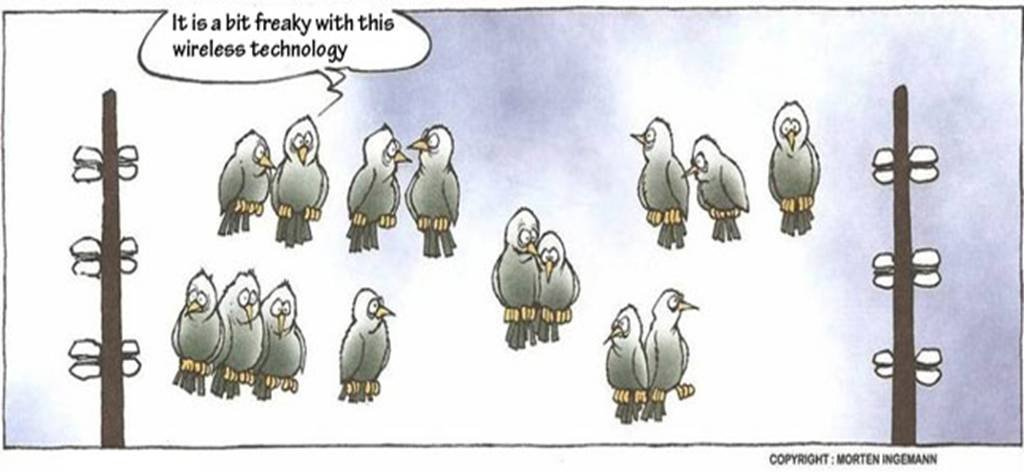

As broadband technology quickly replaces the by-gone days of corded phones and wired infrastructure, the laws regulating the use of wireless technology need to respond in kind. How to go about changing those laws however is a question which is the subject of intense debate on Capitol Hill and in the headquarters of telecom companies throughout the country, especially with several pending court cases which are challenging the authority of the Federal Communications Commission’s role as law enforcer.

Many mobile carriers believe that the entire 1996 Telecom Act must be placed on the scrapheap of obsolete laws, and a completely new legal construct be built from the basement up. Anything less would simply not do justice to the completely new world of communication technology that we inhabit today. Arguing against this type of approach are those that say the wireless industry is just trying to wiggle out of communications regulations that can apply no matter which technology is utilized.

“There is a growing recognition that the communications statutes in place are obsolete,” said Tom Tauke, executive vice president of public affairs, policy and communications for Verizon and a former Republican congressman from Iowa. “There is less consensus on what the new policy should be.”

The wireless industry is pressuring lawmakers to take the plunge and completely remake the legislative landscape, while simultaneously the FCC and the courts are doing their best to apply the old laws to the new wireless world. Verizon has two active court cases at the moment which will help establish exactly what authority the FCC has over broadband. If the court rules with Verizon against the FCC in each of these cases, it could leave the commission with little ability to control the telecommunications industry.

“Verizon is basically arguing that the government has no authority over wireless information services or any broadband offering,” said Blair Levin, main author of the National Broadband Plan.

Verizon representative Tauke says that the FCC is handicapped by the fact that it is trying to apply regulations to a technology that simply did not exist when the laws were created. Chucking the Telecom Act is therefore the best solution.

“The right way to do it now is not to do a ’96 rewrite,” Tauke said. “In this case, what needs to be done is actually completely reshape the statute that governs the communications infrastructure.”

But analysts of the debate say it is unrealistic to assume that the Telecom Act, which was built on the foundation of the 1934 Communications Act will just be tossed into the wastebasket by lawmakers.

“When it’s something this big, you have to count on piecemeal reform,” said Harold Feld, legal director of Public Knowledge. “The fact that some advocate for a new body of laws has impeded progress,” Feld added.